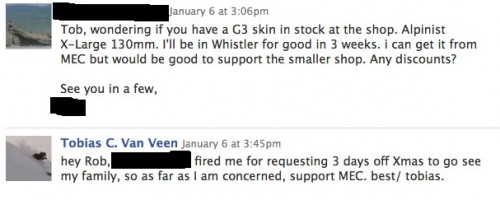

As part of my recent research into the mechanics of dismissal – the ways in which dismissals operate as the modus operandi of precarious labour – I asked around the Facebook network for stories of gettin’ fired. And I was surprised by the response; a good number of friends & colleagues had at one time been ‘dismissed’ from their jobs. Their stories are self-explanatory. It would appear that in most cases, the managerial class deploys dismissal as a means to cover-up structural incompetence. In quite a few cases, employees were misled into short-term hirings; dismissal is an easy way to ignore labour law that protects employee rights.

coffee shop (in 2003?), got hired pre-xmas, promised full-time work by the end of the first week… only got 20-28 hours for the first three weeks… and then as soon as the xmas rush was over, i got told it ‘wasn’t working out’ – but the boss wouldn’t be more specific than that.

slightly different – when working in the convenience store in the UBC SUB, i had an awful, nasty boss, who’d angrily blame her stupid mistakes on the employees, multiple times a day. in the end, i turned up to work ten minutes late, and walked to the front of the line (i think it was new bus pass time, crazy busy) with my letter of resignation, and handed it to her (she was clearly pissed that i was late, and was about to say something rude to me). it read “i can’t stand working for you any longer, you are incompetent and your personality makes working hell. i quit as of now” (words to that effect). i cc’d it to the AMS office, and she was fired a few hours after i resigned – apparently, there’d been complaints about her before. so there’s someone else’s getting fired story, heh…

_Anomie Nous

==

Not an aggressive enough salesperson (basically not being the type of salesperson I hate). This happened at a lingerie/sex shop & at a hippy clothes and knickknack store.

_ Alexis O’Hara

I call the incompetence of supposed managerial superiors ‘structural’ because any corporate structure which does not listen to its employees, and refuses to participate in a two-way dialogue between employees and managers, has already resigned itself to a vertical business model. Management models can be contrasted into two types, both of which are to be found under precarious labour.

The first, the vertical model, communicates from the top-down only. This model can be summarized as command & control. The vertical model uses the psychodynamics of paternalistic authority, manifesting itself in the language of guilt and loyalty, disappointment and approval, and works by way of coercive and usually hypocritical strategies (insofar as the employer, as the ‘good but stern father’, wishes you well – but only insofar as you are ‘seen and not heard’). Usually the failure of the vertical model is self-evident. Without any kind of dialogue, managerial power is absolute. Employee scheduling is usually a mess; staff are kept 24/7 on call for shift changes. Fear operates as a motivator due to constant demands on regular scheduling. In this respect, the vertical model has changed since the 20th century; one’s ‘hours’ are not set in stone and can change at any time. Examples are made, of course, out of those who raise questions or attempt to engage in dialogue. For the most part, the vertical model is still the most prominent, and to be found in retail, etc.

i got “let go” from a residency recently for playing house..

_ Deejay Tripwire==

new tattoo

_ Maria Herrero

The second, the deceptive horizontal model, is a supposedly more open, and relatively newer model of employee–managerial relations, and follows a consult & direct procedure. Open discussions are held with staff; employee ideas are explored. In a company like Google, (paid) time is even set aside to follow employee initiatives. In this model, there is a semblance, if not an actual amount of respect, inclusivity, negotiation, and ultimately, some degree of understanding between managerial and employee subject-positions. However, the advantage and the disadvantage of this model are the same, which is why it is deceptive: ideas percolate up. Whatever the employee initiative, it is property of the company, and not the employee, and the employee can easily be dismissed/shuffled out once their initiative has been overtaken by the corporation’s interests. This model is often found in ‘progressive’ hi-tech industries, the film industry, arts, music, academia and other creative industries, and in many respects is the model of precarious labour itself in its alliance with cognitive labour. In this sense, the deceptive-horizontal model is precisely what workers of the ’60s onward fought for: the mobilization and relaxation of labour time, more collective involvement in decision-making, and increased involvement in and responsibility for corporate operations. But this has had the downside of mobilizing all time into company time. All employee ideas are pre-owned by the company, and at its worst, this horizontal model is that of a cognitive sweatshop, as seen predominantly in the gaming and programming industries. Expect long hours without credit for brilliance; the managers steal the latter from their team, using what percolates up from below to advance their own careers/interests.

accusations of abusive language

_ Michelle Fearless==

In clubland, I once had my wages raised (without asking for it – I was told I was worth it) and was told a month or so later that it was too expensive to keep me, so they “let” me “go”.

_ Hillegonda Rietveld

Tags: anthronomics, cognitive labour, copyright, precarity

.tinyUrl for this post: | https://tinyurl.com/y38924mp .

RT

RT

Nice assessment. In a crude, generalized way, this reminds me of Zizek’s understanding of the two types of authoritative punishment. The first being the authoritive figure who makes a direct demand followed by a clear consequence: ‘clean or room or else…’ The second being a suggestive demand and consequence: ‘you should clean your room, but really, it’s up to you.’ In both examples the demand and consequence are the same but they’re just implemented differently. The first being direct and ‘vertical’; the second suggestive and ‘open’.

Foucault’s ‘Discipline & Punish’ posits a similar set-up. Interestingly, both Foucault and Zizek prefer the first mode, calling the second psychological punishment.

I know your argument has more to do with the functions of the workplace, but there are some crossovers that I find interesting, especially since one of my jobs fits the second category and the other is a hybrid of the two.

Spencer, indeed, thanks for making the reference to Zizek & Foucault. What I am particularly enjoying in thinking about my own experience and others in relation to contemporary labour is first thinking the experience, then going and looking up the theory. And more often than not, the philosophical approaches I have valued the most in the past are those that are confirmed once again in their experiential testing. The approach is kind of philosophy/political theory-by-ethnography (I called it ‘anthronomics’). Point being, thanks for your considerate reference, as it’s spot on, and puts a savage grin on my face knowing that the theoretical pursuits too often discredited for being lofty or lacking evidence are easily born-out on the shop floor…

I should add that the first, vertical mode is more often than not hypocritical rather than direct. My experience has born out not Zizek’s ‘direct father’ who issues a command, but a covert command which, once transgressed results in discipline. So I think even the vertical model has shifted in precarious labour to using the ‘psychological’ tactics of the second. And the second, deceptive-horizontal model, for all its faults, offers the possibility — even in its impossibility, ie as a blockage — of infiltration, intervention, subterfuge. Of course it’s like Angel Season 5 (if the series rings a bell): once you are given the corporation, as the good guys, can you wield such an evil tool for good? Or does it corrupt you as soon as you are implicated within it? I’d still prefer a workplace where both (a) the rules are clear but (b) they are open to negotiation insofar as the staff *makes their own rules*. But that’s basically the principle behind collectivist organisation … it’s called (direct) democracy.

[…] « data on dismissal: getting canned […]

@gdpproject data on dismissal & business ontology (or why Xmas gets you fired): http://bit.ly/8e0c2f | http://bit.ly/8lziyU